In cities and villages across Mozambique the huge need for aid and assistance is not being met

The main road connecting the cyclone-devastated Mozambican city of Beira to neighbouring Zimbabwe comes to an abrupt end. A section almost 100 metres long is almost entirely under water, an angry muddy gash where the tarmac was ripped away by the floods and raging currents.

A week after the onset of Cyclone Idai, as the waters have receded in some places, some of those trapped in villages in the midst of the flood waters have at last managed to get out.

Near a cluster of wood canoes pulled up on a ‘beach’ next to the road, Pedro José, 47, emerges from the waters with a bag on his head. He says he walked 12 kilometres from his hamlet of 45 people to reach the road. He indicates back the way he came.

“There are still many people back there.”

Shattered by his journey, he is unwilling to say more.

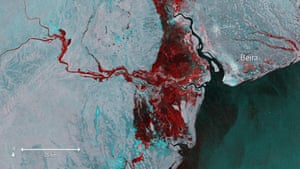

The waters that hit villages like Pedro’s poured down from the higher elevations across the border in Zimbabwe, overwhelming the Pungue and Buzi rivers that crisscross this area of low plains, carving new channels and creating an enormous inland lake more than 125km (78 miles) long.

Survivors tell similar stories of being trapped or driven from their houses, many of them now angry at the slowness of the rescue effort.

They have heard the rescue helicopters fly over, sometimes seen the few boat rescue teams that have been dispatched, but what they need most – food, clothes and shelter – has yet to arrive, despite the mounting international rescue effort centred on Beira.

The further you drive away from Beira the worse it gets. At first crowded food distribution centres are visible in the larger settlements, the ground littered with uprooted trees and the metal torn off the roofs of the more solid structures.

But by the time you reach the village of Tica, where the road to Zimbabwe abruptly ends, it is a much bleaker picture. The villagers – washed out of their roadside homes – have set up makeshift shelters made from black plastic sheeting and corrugated roofing on the hard shoulder.

Their houses are still just about visible, with walls collapsed and roofs caved in where anything has survived at all.

“We don’t have anything,” says Josef Marius Jafate, a 29-year-old farmer who, like many of those in this impromptu roadside camp, is surviving solely on the river fish he can catch.

“We don’t have rice, or flour or any clothes. We need shelter. When is the help going to come?” he says.

Josef explains that he fled his small grass-roofed house on Saturday just over 24 hours after the cyclone had struck.

“The water started coming in and we had to escape with what we could carry to the road. We have been here ever since.”

The villagers’ complaints reflect a rescue effort that is still chaotic and under-resourced, short on helicopters and boats.

And while Beira remained a scene of widespread damage on Thursday, the real question is what devastation has occurred in the floodplains of places like Tica, which have been affected by a disaster some senior aid officials are comparing to Hurricane Katrina.

Even those involved in the aid effort admit they are far from having a proper picture of conditions in large parts of this densely populated rural region.

Drone footage captured by a photojournalist travelling with the Guardian hinted at what lies beyond the road: water for as far as the eye could see and a line of simple houses flooded to the rooftops.

The scale of the disaster has been hard to comprehend even for those who have been flying aircraft over the affected areas.

Satellite images released on Thursday morning show a vast lake 125km in length and 25km wide, where rescuers continue to struggle to reach many areas, where an uncertain number remain on rooftops and in trees.

According to rescue coordinators almost 1,000 people were rescued on Wednesday, including 700 by boats made up in part by the Indian navy.

Describing the scale of the disaster, Gerry Bourke of the World Food Programme tells the Guardian that the growing international rescue effort still does not know how many people remain trapped in the flood waters.

“That’s the question. This was one of the most densely populated areas in Mozambique when the cyclone hit.

“There is huge urgency now to get to people. Given the size of the lake we are seeing on the satellite images we need to ask where are the people who were living there?”

Those with the closest view have been the rescue helicopter crews flying out of Beira’s airport.

Gerhard Louw, a winchman on a helicopter run by Rescue South Africa, an NGO involved in the rescue efforts, described what he had seen in days of flying over the flooded plains.

“The waters have started to recede now, it is waist deep rather than touching the rooftops. As you fly you see clusters of people everywhere. Twenty on the solid houses. Fifty plus on the bigger roofs.”

Louw flew rescue mission around Buzi, one of the worst affected towns, which he described as having only a single dry area.

“Where canoes have got to areas we leave them to get on with it and lift people in the most need.”

And the need is massive. Out of 600,000 people assessed to require assistance, many may be in life-threatening circumstances.

Underlining the scale of the problem is the plans being examined by the UN agencies and Mozambican authorities to build two massive reception areas to accommodate 400,000 people.

But the biggest unanswered question is the death toll. Villagers who spoke to the Guardian told of fatalities but could not estimate how many aside from saying that whole villages had disappeared.

Only when the floods recede will that accounting finally take place.

The post ‘We don’t have anything’: the fight for survival after Cyclone Idai appeared first on Zimbabwe Situation.